- Home

- Kōji Suzuki

Death and the Flower

Death and the Flower Read online

Copyright © 2014 Koji Suzuki

All rights reserved.

Published by Vertical, Inc., New York

Originally published in Japan as Sei to Shi no Gensou by Gentosha, Tokyo, 1995.

e-ISBN 978-1-941220-37-5

Vertical, Inc.

451 Park Avenue South, 7th Floor

New York, NY 10016

www.vertical-inc.com

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Disposable Diapers and a Race Replica

Irregular Breathing

Key West

Beyond the Darkness

Embrace

Avidya

Afterword

About the Author

Disposable Diapers and a Race Replica

1

My wife’s figure as she tiptoed out of the room stirred the humid early-morning summer air. Despite her efforts not to disturb me, even a slight shift in presence always woke me. Pausing at the threshold, she took form on my retinas as a darker shadow in my dim field of vision.

“Oh,” she said, sounding slightly surprised. “I didn’t mean to wake you,” she apologized, yet didn’t meet my eyes, her line of sight wandering in the rear closet instead. What was she staring at with such vacant eyes, thinking what? Most likely she was worried over something stemming from another set of worries, as she was wont to do, rendering herself incapable of action. Anxious that her skirt was too gaudy, for instance, she might be imagining each of her colleagues’ gazes until she couldn’t get going. It had been that way last morning, too. She’d pull out something from the back of the chest of drawers, stare at it for a while, then put it back. Then take out something else and put it back as well. She appeared ready to skip off work and repeat the ritual all day long had I not told her to knock it off.

“Hey,” I called out in a subdued tone, trying to snap her out of whatever meaningless scenario she was ensnared in this time. As if on cue, she pivoted to face me, said “see you later,” and made to walk out the front door.

“Hold on a minute.” I got out of bed and went after her, stopping her at the foyer. “I go to the daycare today, right?”

She nodded twice.

“I’ll have dinner at home, then from seven to nine I’ve got that private tutoring job,” I reminded her. “I’ll probably be home by ten, but you don’t have to stay up for me.”

“Won’t he just blow it off again?” Her sly smile was a sign that the chain of worries binding her just a moment ago had evaporated.

“I don’t care if he never shows up. I’ll still get that tuition money.”

I had started tutoring an eighth grader this past April, but as soon as summer vacation came he started blowing off his lessons, never coming home at the appointed hour, probably out goofing around somewhere. Last week and the week before, too, I had waited in his room in vain for two hours.

“Oh, I almost forgot. We’re out of disposable diapers. Would you mind getting some?” my wife requested.

We normally used cloth diapers on our ten-month-old daughter, but for bedtime we went for disposable diapers as they had better absorption.

“All right.”

“Okay, I’ll see you later.”

My wife waved exaggeratedly and walked out, her heels echoing loudly in the apartment building’s staircase. The sound seemed needlessly, intentionally loud, as if she were feigning high spirits. Like the eyes of a cat, her mood changed rapidly. Just when she seemed to be staring into a black abyss with vacant eyes, she’d burst with innocence. Her rushing down the stairs with her exterior and interior utterly imbalanced always set me on tenterhooks.

My wife had received a diagnosis of neurasthenia six months before we were married. Thankfully, her nerves seemed to have stabilized lately. While she was pregnant, she suffered bouts of insomnia and tinnitus, but perhaps childbirth altered her constitution as she said she slept quite well now. Certainly, her face looked much brighter these days when she went off to work. It seemed we had made the right decision.

With the baby’s arrival, one of us had to quit our jobs. We could only leave the baby at daycare from nine to five, after which we would have to hire a nanny for two-fold childcare. The combined cost would easily eat up one of our salaries. Whereas I had switched jobs repeatedly ever since graduating from college, my wife had held a steady job as a school librarian. She didn’t much enjoy working with people and I was hesitant to rob her of a workplace she was accustomed to. I was also concerned that her nervous condition might relapse from the strain of raising the child alone. Every single move the baby made would sow seeds of distress, and it was clear she’d worry herself to her wit’s end. There was a decidedly high risk of her developing maternity neurosis.

As it happened, around that time the event planning company I worked for was in so much trouble it was on the brink of writing rubber checks, which gave me an incentive to quit. That was in April. Since then, I worked diligently every day, taking care of nearly all childrearing duties while also working part-time as a gym trainer and as a private tutor.

I heard my daughter roll over in her sleep. It was just after seven—two more hours until daycare. Wanting to doze off a bit longer, I burrowed under the covers right next to my daughter, cupped my hands around her head, and drew her closer.

People often say she looks just like me. I myself am surprised by how similar her features are to mine, even in the growth of her eyebrows and peach-fuzz hair. Now our uncannily similar features were laid parallel to each other. While I gazed at her face, I detected the shadow of my father who had passed away the month before. He’d been a textbook tyrant who’d sit cross-legged like a feudal lord and hurl abuse at his wife and children. It felt like an inconsistency that the vestiges of such a man should exist in my sweet little daughter. One was vulgar and forceful, while the other was utterly adorable. And here was I, the intermediary between their blood.

At eight o’clock, I rose and reheated the baby food my wife had prepared. I then woke up my daughter, sat her on my knee, and filled her belly spoonful by spoonful much as a mother bird does for a chick. During the monotonous routine I turned toward the bright sunshine out the window and went over the course of tasks planned for the day.

After dropping my daughter off at daycare at nine, I would return home to do laundry. The cloth diapers had to be washed separately from our underwear and clothing, requiring two loads. Once that was done I had a shift as a trainer at a gym in Meguro until four. In the morning, however, there were very few clients so I would use that time to work out. I really only ended up working with clients for the three afternoon hours. I was single-minded in my training regimen since I’d been admitted to the weight-lifting competition hosted by Kawasaki City. In order to win in the 160-lb class, I assumed I had to lift 1,200 lbs. total across three events: bench press, dead curl press, and squats. Victory was unlikely unless I was able to set a new personal record.

I paused the feeding and rotated my right shoulder. When I kept my elbow pointed towards the ceiling, I felt a slight pain run through my joints. I must have overworked it the day before, rousing an old injury that not even a full night’s rest had eased. Take it easy today, I admonished myself. I wanted to come in at number one no matter what.

I thought objective recognition of my physical prowess would reaffirm my value for my family.

After the gym shift I would go to the daycare to retrieve my daughter at five. I would pick her up as she crawled to cling to me, strap her into the baby sling on my chest, head home to the apartment, and wait for my wife to return from work. After an early dinner, I would go to Ota Ward for the tutoring session at seven. That bastard Masahiro would

probably stand me up again. Since I already knew that was the likely outcome I didn’t care to go at all. Time was ripe for a decision: Should I continue working with the Kawaguchi family, or should I find another client? Whatever the case, I had to decide on a stance by the end of the week.

2

The setting sun warmed the back of my jacket as I entered the final approach to Tokyo. The traffic was congested in both directions on Maruko Bridge, which spanned the Tama River, but on a 250-cc motorcycle I had little trouble negotiating the rush-hour roads.

In order to minimize any injuries in case of an accident, even during the summer I always wore gloves, a jacket, and boots. Fitted with duo-toned full fairings stretching from the headlights to either side of the engine and modified into a single seater, my bike was a race replica good enough for the circuit. It wasn’t the kind of bike a thirty-something man with a wife and child would normally ride. Back when I’d purchased it, it was the standard for a two-stroke bike. There wasn’t a less aggressive model available.

Getting off the bridge and crossing the first intersection I saw a large billboard for a drugstore. Just then, my wife’s voice echoed in my mind.

We were out of disposable diapers.

I switched on the directional, pulled over to the left of the street, and parked. I had forgotten all about her request.

The bungee cord that I used to lash luggage to my bike still had to be there in my backpack. I wanted to buy a big economy-sized set, but I wondered if I could even attach the cardboard box to the rear of the bike. From my experience with touring that included overnight stays, I knew that a certain amount of luggage could fit on the bike. It was my vanity that itched slightly. Diaper boxes were always handed over to the customer with nothing more than a proprietary “paid” sticker as they didn’t have large enough shopping bags. Illustrations of naked babies tied to the back of an intrepid race replica? At dusk, with the sun still lingering above the horizon, the discordance would surely attract attention.

But you can’t raise a child if you’re overly concerned with appearances. I got off my bike, took an armful of the discounted diapers stacked high by the entrance, went to the registers at the back, and lashed the diapers to the rear of the bike.

As soon as I walked through the door I was greeted by Mrs. Kawaguchi, who looked to be on the verge of tears. I read from her expression that her son hadn’t returned yet for the tutoring session that was supposed to begin. I could sense her helplessness from where I stood, and just witnessing her deep embarrassment was exhausting.

“I’m so sorry, sensei. His older brother’s gone to look for him. Won’t you please wait inside a while?”

I’d heard the brother was a bit of a troublemaker himself in junior high who’d matured some after getting into a mid-level public high school. Now he was out searching for his kid brother who’d fled the tutor, perhaps having a clue as to where he’d gone.

After being led to the second-floor study I placed my daypack, filled with textbooks and worksheets, at the side of the desk. The desk itself was in disarray. The report card he’d received at the closing ceremony at the end of the semester was still in the same spot it had occupied last week. I indicated the report card with my chin as his mother brought in a cup of coffee.

“I guess that’s the reason behind all this.” The conspicuously placed report card had been folded repeatedly, a symbol of Masahiro’s protest.

“I thought it’d get better …” his mother trailed off ambiguously and looked out the window. Fretfully checking the gate hoping her son was back, she apparently spotted the motorcycle adorned with diapers parked outside. “Oh, sensei, you have a baby?” she asked, her voice suddenly high-pitched.

“Yes. A daughter. She just turned ten months old.”

“You’re so lucky to have a girl. Boys can be very hard.” Her words carried the weight of experience. She was clearly at a total loss about her younger son. That’s why I had been summoned.

After quitting my job in April, I’d decided to re-register as a private tutor in Tokyo. I’d taken on such work starting in college, and after graduating I’d done short-term intensive tutoring sessions between jobs as I’d frequently changed occupations. No other job paid better hourly rates while still allowing me to receive unemployment benefits. As soon as I re-registered, I received a call. The client was not looking for a student tutor but an experienced adult, so I was a candidate.

The first time I visited the Kawaguchi residence along with a representative from the agency, Mrs. Kawaguchi showed me a picture drawn on the answer sheet for a final exam. In a box at the top of the page the name “Masahiro Kawaguchi” was scrawled in abysmal handwriting. The rest of the sheet was blank except for an illustration of male genitalia. There was a big “0” above his name in red ink, with two lines under the number. The crude drawing that ran over the tidily arranged answer column for the math problems was childish in the extreme, inferior to specimens found on the walls of public bathrooms. I could see why this drawing was the focus and not the fact that Masahiro earned nothing but zeroes in math and English. At the end of the term, Masahiro’s mother had been called in by the principal, who sternly warned that the boy was not likely to be allowed to move on to high school at this rate.

It was easy to imagine how despondent Mrs. Kawaguchi must have felt when the principal and the homeroom teacher showed her that drawing. For a mother of two teenage boys she seemed somewhat weak and unable to properly govern boys. She probably indulged their every whim until they felt nothing but contempt for her.

After seeing the picture, I decided to modify my educational methods. Some male junior high students don’t respond until you exhibit brute strength. As soon as I realized Masahiro was one such student, he never stood a chance of taking advantage of me. If he even tried to talk back, I tossed him to the floor and bent back his elbow, holding the lock relentlessly until he apologized. While I resorted to coercion, I also shored up his weak grasp of fundamental course work and praised him lavishly when he arrived at the correct answer. Thus alternating between carrot and whip, I tamed Masahiro to the point where he would complete seven-tenths of the homework I gave him. Teaching isn’t that exhausting when there’s visible improvement. Seeing students fully respond to all the energy you pour into them is similar to the rewards of raising a child.

As expected, he scored 14 on math and 11 on English on his mid-term exams. The mother was immensely excited when she saw the scores. I lost count how many times she said, “Thank you so very much.” I had become a messiah to the Kawaguchis simply by getting the kid’s grades up. That day Masahiro and I took a break from studying. We sat in front of the TV and watched a boxing title fight together.

By finals, his scores had improved again. He scored 19 in math and 17 in English. While those could hardly be considered high scores, for a student who’d only received zeroes it was a decent improvement. I had anticipated that his failing grades in both math and English would improve into D’s this time around. But the report card he received at the end of the semester still showed a row of F’s. He was not rewarded for the first effort he’d ever made towards studying. Yet I was the one who was crestfallen when they showed me the report card.

“Can’t be helped, eh, mister?” Masahiro said with a smirk, seeming strangely unaffected, but I couldn’t help feeling frustrated. If his grades had risen, our sense of teamwork would be solidified, improving his study habits and thereby easing my task. Four months of violence-steeped investment in his education had been washed down the drain.

The following week, Masahiro didn’t come home at seven, the appointed hour. The week after that, he blew me off again. As I had feared, his report card completely destroyed any enthusiasm he’d gained. I wasn’t a part of his family; I was simply a tutor hired to work with him once a week from seven to nine, and if the student wasn’t home, there was nothing I could do. Ordinarily, you’d expect the father to come tie his son to the desk if need be, but I had yet to se

e any trace of the man.

As if he’d been waiting for his mother to bob her head and exit the room, Masahiro’s brother came to stand at the doorway and looked at me hesitantly.

“Yes?” I said, looking up.

“Can I ask you a question?” He held out a textbook. Apparently he wanted me to teach him in his brother’s place.

“Sure,” I said, placing the book that I was reading down on the desk and waving him over. I gave him some pointers on how to work a translation. When we paused for a moment, a thought suddenly occurred to me and I asked, “Weren’t you out looking for Masahiro?” I didn’t know exactly when the brother had returned, but he was back far too soon if he’d indeed gone on a search.

“It’s no use. That idiot’s with Fujishima,” he said bashfully, glancing down.

“Fujishima?”

“Big brother of one of his buddies. He’s in a biker gang.”

Fujishima. I had heard Masahiro mention the name several times.

He gets pissed real easy. He’s mad dangerous, Masahiro had said, his eyes focused on something far away.

“Do you know where he is?”

“Yeah, I think.”

“Where?”

“Étranger.”

Probably the name of a coffee shop or something that the gang haunted, it was no mystery why Masahiro’s brother hadn’t tried to bring him back even knowing where he was. The brother was afraid of Fujishima. Seeing them together, he must have slipped back home without so much as calling out to his kid brother.

“Is it nearby?”

“About a ten-minute walk. Go down Nakahara Street toward Tama River and it’ll be on your left. It’s such a lame old coffee shop you can’t miss it.”

It would take less than five minutes on my bike. It was almost nine. I had no intention of dragging him back and tutoring him, but I didn’t mind checking on him on my way home.

As I was getting ready to leave, the kid smiled broadly with a baby face that resembled his mother’s and said under his breath, “You’ll be fine, sensei.”

Death and the Flower

Death and the Flower Spiral

Spiral Loop

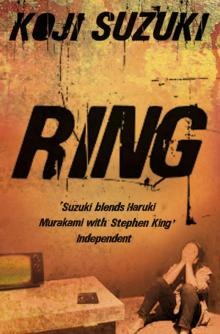

Loop Ring

Ring S

S The Complete Ring Trilogy: Ring, Spiral, Loop

The Complete Ring Trilogy: Ring, Spiral, Loop Birthday

Birthday Edge

Edge Dark Water

Dark Water The Complete Ring Trilogy

The Complete Ring Trilogy