- Home

- Kōji Suzuki

Edge Page 3

Edge Read online

Page 3

In all of the ink paintings I’ve ever seen, there’s never a single person depicted, even off in the background. Why don’t people ever appear in ink paintings?

When Jack realized that his cup was empty, he refilled it with hot water from the pot. Even though the heat was controlled by a thermostat, he couldn’t shake the sensation that the room was getting colder by the minute.

In the microscopic realm of elemental particles, objects ceased to be objects. When you became deeply immersed in that world, you saw that the visible one constituted only the merest slice of the ever-repeating phenomena of life and death, and concepts of permanent existence quickly became a long-lost dream. The real number line seemed one-dimensional, but between the integers three and four, for example, there existed infinite irrational numbers, transcendental numbers and so forth, writhing and wriggling like microscopic organisms. As a physicist, Jack didn’t see the number line as one-dimensional. Nor did he perceive it as two-dimensional or three-dimensional. Beyond the strings of randomly repeating numbers, he sensed a bottomless abyss that almost seemed to imply a pathway to another dimension.

A hypothesis had pushed its way into Jack’s mind, but it was an idea he preferred not to speak aloud.

If we look at the number line in terms of the quantum world, fluctuations in the value of Pi might be possible.

What could the odds have been of a world like ours emerging through the Big Bang and the birth of the universe? Jack’s friend Lee Smolin estimated them to be one in 10ˆ299, while the arithmetic-loving Roger Penrose had come up with the figure of one in 10ˆ(10ˆ123). Numerically the values were vastly different, but the implications were the same. The odds for the string of coincidences necessary to create our universe were basically nil.

The universe was comprised of just two types of constructs: astronomical entities and life forms. Mountains and rivers were part of astronomical entities, while tools were the creation of humans and other life forms. Constructs of life and astronomical entities were supported by infinite physical constants. These could be compared to adjustable dials whose fine-tuned calibrations served to maintain the world as we know it. Moreover, the majority of physical constants were related to Pi through basic equations.

Jack felt as if an icy lump in his stomach was melting, sending rivulets of cold throughout his body. He had begun shivering intermittently, and soon the trembling became constant and his teeth chattered violently.

It was only a hypothesis. But just contemplating the implications, Jack was so deeply disturbed that he couldn’t stop shaking.

There had been a change in the value of Pi. And it involved a string of the heretical number that had struck terror in men’s hearts since ancient times: zero.

This is just a new bridge humankind must now cross, Jack told himself. In his mind, the semi-circular bridge in the ink painting quietly crumbled.

Chapter 1: Missing

1November 5, 2012

Saeko Kuriyama awoke with a start, her heart thumping wildly. Almost as if her heart had taken over her entire body, its pounding emanated outwards, causing her breasts to twitch with its surging pulsations. Today, yet again, Saeko was unable to get up for several moments after awakening.

When she opened her eyes, the shapes around her were still dark. She remained motionless at first, trying to catch her breath before she reached for the clock on her bedside table. It read 9:11 a.m. She had overslept by quite a bit. As the details of her room began to come into focus, the darkness she had perceived initially began to fade.

For a full twenty minutes, Saeko remained under the covers and waited for her pulse to stop racing, ignoring both her need to urinate and the dryness in her throat. The refrigerator was only several meters away, but it seemed much farther. The thought of cold mineral water was appealing, but Saeko couldn’t yet bring herself to move.

Life had become so painful, it was unbearable. Lately, Saeko felt the same way each morning. Especially as the seasons shifted from autumn into winter, the wretchedness of living alone grew ever greater, almost tearing her to pieces. Her pent-up misery thrashed about wildly in her searching for an outlet.

Go ahead. Hurt me. Take my life, please.

Death seduced her. She lacked the courage to commit suicide, but if the natural flow of things were to lead her to death, Saeko wouldn’t resist at this point. She felt no attachment to life. Her reasons were indistinct, but they weren’t impossible to pinpoint.

The divorce she had gone through six months ago had done more damage to her, emotionally and physically, than she had ever anticipated. The idea that she was unfit for marriage deeply marred her confidence, intensifying her isolation. It convinced her that she was missing something other people had.

“There’s something deeply off about you. You’re like a transform fault. A human Fossa Magna,” her husband had said once in a fit of exasperation.

“The Fossa Magna is a great rift valley, not a transform fault,” Saeko had corrected him coolly.

“That’s exactly what I mean.”

He’d made similar remarks a number of times, though not exactly framed in those terms.

“You’re bizarre. You’re not normal.”

After being told the same thing enough times, Saeko had begun to suppose he might be right.

“Why do you always have to compare people? It’s driving me crazy!”

That was the only accusation that had really struck Saeko to the core; he had managed to hit the nail right on the head. When Saeko and her husband had lived together, Saeko had compared him to her father at every turn. Whenever she observed her husband failing at something her father could have easily done, Saeko deducted points from an imaginary scorecard.

No man on earth could live up to my father.

Even now, it was still true as far as Saeko was concerned. The pain of divorcing her husband of five years was nothing compared to the overwhelming loss she’d experienced when her father had gone missing. The amount of tears she shed now was paltry in comparison. Eighteen years ago, Saeko’s father had vanished suddenly without any explanation. He had been Saeko’s guardian and her only living relative. To this day, she hadn’t the faintest clue what had become of him or whether he was alive or dead.

Saeko’s mother had died thirty-five years ago during Saeko’s birth. From what she understood, there had been some sort of medical mishap, but Saeko’s father said little about the incident.

My loneliness began at birth.

Viewed in that light, it all added up. Saeko had come into the world just as her mother had left it, and her father had showered her with all of his love. But that had only intensified Saeko’s despair when her father had suddenly disappeared. It was as if a lid had been closed on her life, sealing her in darkness.

Perhaps that was why Saeko sometimes found herself seized by the sensation of being trapped in a dark, constrictive space, unable to move. It wasn’t a dream, a hallucination, or sleep paralysis—it was much more real and immediate. It was as if she were enclosed in some sort of gelatinous membrane; she could feel its rubbery walls. She huddled within it like a fetus, blind, unable to move her arms or legs, and in her stillness it was as if she were the last person on earth, wracked by a desolation that made her immobility worse. After a few minutes, Saeko usually recovered her ability to move, and the pounding of her heart gradually receded as well.

Saeko crossed her hands over her chest and took steady breaths, trying to persuade the palpitations to subside. As the fingertips of both hands grazed her breasts, she suddenly became aware of a slight, unfamiliar discrepancy in their symmetry as her fingers encountered a hard, tiny lump on the outer side of her left breast.

She drew her hand away quickly and lay motionless, gazing up at the ceiling. She had a habit of holding perfectly still and focusing inwards when faced with an ominous premonition—a condition she liked to call “going into a quantum superimposition state.” She wove together affirmations and denials both consciously and un

consciously until a single conclusion emerged. Then the message traveled from her mind to her body.

Saeko unfastened two buttons on her pajamas, slipped a hand through the opening, and carefully explored both breasts—breasts that hadn’t been caressed by a man for a year. Beginning at the nipples and making three progressively larger circles, Saeko once more detected the lump on the underside of her left breast. She hadn’t imagined it. It was unmistakable and right where she’d felt it earlier.

Oh, no.

Saeko didn’t know what breast cancer would feel like, but she focused inwards, straining to detect some sort of unfamiliarity. Her digestive system, respiratory system, circulatory system, urinary system, reproductive system, nervous system … She pictured each set of organs in turn, trying to perceive the birth and spread of a malignant tumor. But of course she didn’t feel anything. She gave up and instead tried to remember when she’d last had a check-up.

Two years ago. Maybe three. Her numbers had all been fine. In fact, the data had shown her to be almost too healthy for a woman in her mid-thirties.

At the thought of breast cancer, and the realization that death might lurk just beyond it, a chill ran up Saeko’s spine. Just moments ago, she had denied to herself that she feared death at all, but that fearlessness evaporated with the eerie sensation of discovering an abnormality in her body.

She had never had much libido, but as she stroked her breasts, she imagined her hands as belonging to some faceless man. In an instant, the possibility of death and sex seemed to converge in a single spot in her breasts.

It’s probably mastitis, she told herself. Banishing the fear of breast cancer with a convenient alternative, Saeko rose from her bed. Lying around gave her mind too much freedom to wander. Better to get up quickly and get to work. She had to keep moving if she wanted to forget her torments. Some people worked to make money. Saeko worked to live.

Currently, she was assisting with a television program. She’d debated whether or not to get involved, but before she knew it she’d been drafted into the project as a de facto team member.

Still seated on her bed, Saeko reached for the remote control and turned the TV on. As the sound came on, the words “breast cancer” evaporated from her mind, though her left hand continued unconsciously stroking her breast.

The incident had been featured on a tabloid-style TV special that February. Just like today, she’d been lying around in bed and had switched the TV on with the remote. The screen had lit up with the image of a stately farmhouse set against the vivid greenery of a hillside. Then too, the time had been just after 9:00 a.m.

Saeko remembered the program with astonishing clarity. The house was of a traditional Japanese architectural style, the kind you saw sometimes in mountain villages. The female reporter walked slowly up the gentle incline of the paved road in front of the house as she described the incident to the viewers.

“Two weeks ago, a family of four vanished from this house in the suburbs of Takato.”

Instantly, Saeko was riveted. The words penetrated deeply into her consciousness, rudely stirring up memories of the past: the chirping of cicada a vivid cascade, the steep stone stairs leading up to a shrine, the thick canopy of giant cedars forming a ceiling overhead, beams of blinding summer sun streaming down through the gaps …

Interrupting Saeko’s memories, the female reporter had continued, holding a microphone in her left hand and pointing towards the house with her right, her face a mask of gravity: “The entire Fujimura family of four has disappeared from their home. They left dishes freshly washed in the kitchen, the table set with tea cups, the bathtub full of water, and the laundry machine full of clothes. There are no signs that the house has been ransacked. Everything here is perfectly normal, except that the house’s inhabitants are gone. Nobody has any idea why the Fujimuras would have disappeared. They were well-to-do, as you can see. They had no debts, no ties to any religious cult. Their disappearance is an absolute mystery.”

A relative of the family was shown making the standard remarks: she had no idea why the family had disappeared, and she prayed for their safe return. Then the female reporter reappeared.

“We all hope the Fujimura family is safe.”

From there, the show shifted abruptly into a story about two popular celebrities getting married. Saeko had lost interest and changed the station.

For a while, the disappearance of the Fujimura family was featured on various TV gossip shows and magazine close-ups, but after about a month the media attention had waned. No new developments had come to light, and there simply wasn’t any material to support further coverage, even though public interest in the incident remained high and the entire nation was aware of the story.

Time passed without the investigation making any headway, and before long, nearly ten months had transpired without anyone learning what had become of the Fujimuras.

Saeko had never expected to become involved with the case. But that July, just half a year after the family’s disappearance, she had received a phone call from Maezono, chief editor of the Sea Bird monthly magazine at Azuka Press. Saeko knew Maezono wanted to offer her an assignment even before the meeting. From the tone she picked up on the phone, it was probably a substantial job. Maezono had even hinted at the possibility of serialization.

At the front desk of Azuka Press the next day the receptionist buzzed Maezono’s office. When the large woman came waddling down the stairs, the first words out of her mouth were: “Let’s grab some lunch.”

She invited Saeko to a nearby Italian restaurant. It was a trick of the trade—treat the contractor to a meal, then gently propose a deal over a full stomach. When they had finished eating and were sipping their postprandial coffees, Maezono finally got down to business.

“It’s about the Fujimura family’s disappearance. You’ve heard of it, I assume?”

“Of course.” Saeko’s response was immediate.

“Well? Are you interested?” Maezono probed, not skipping a beat.

Was she interested? To Saeko, nothing was as critical as a missing person case, and Maezono knew it.

In response to Saeko’s silent stare, Maezono passed her a sheaf of papers. “If you don’t want to do it, just say so. But I don’t know anyone more qualified for this assignment.”

“You want me to do an investigative report on the incident?”

“Yes.”

“I’m interested in the case.”

It was definitely an issue that Saeko cared about. But considering her own emotional health, perhaps it was one she needed to avoid. If she wrote about a missing persons case, it was bound to stir up memories of her father’s disappearance.

Saeko had conducted an exhaustive search for her father, so she knew a thing or two about looking for missing people. It seemed Maezono was scheming to add such cases to Saeko’s fields of expertise as a reporter.

“Will you do it? I realize this is a sensitive topic for you. But sometimes confronting an issue head-on is the best way to overcome it. Like that article you did on your divorce.”

That May, just after her divorce, Saeko had been offered an opportunity to publish a humorous account of the experience in a sports tabloid. Upon marrying, Saeko had quit her job as editor of a science magazine to pursue an independent career as a freelance reporter. The offer couldn’t have come at a better time, since she needed to establish a broader base as a writer, and writing a tongue-in-cheek story about divorce was definitely a foray into new terrain.

At the time, Maezono and Saeko had never met. But when the article came out, Maezono read it and immediately contacted Saeko. Maezono was forty-two and also divorced. She told Saeko that the article had resonated with her.

I liked how you used humor to weather your pain and suffering.

Having tasted the same bitter fruit, the two women hit it off from the moment they met, laughing it up over their ex-husbands’ foibles and idiosyncrasies. Immediately, Maezono had begun to assign Saeko writing jobs,

motivated less by her desire to help Saeko survive economically as a single woman than by her appreciation of Saeko’s work ethic and meticulous research.

At the time, Maezono had just recently been appointed editor-in-chief and was striving so zealously to increase readership as to raise a few eyebrows. If she succeeded, Maezono felt she would validate the board’s decision to select her for the job. If she failed, not only did she stand to lose her job, it would also compromise the standing of the board members who had supported her.

In order to sell more subscriptions, Maezono came up with the idea of giving the magazine’s soap-box tone a makeover. There was a limit to how many copies they could sell with pages primarily designed to appeal to male readers. The fastest way to increase readership was to conquer a broader demographic. Maezono’s battle plan was to engage the interest of female readers by publishing detailed investigative reports of the type of incidents featured on the local news pages.

The plan worked. The magazine’s subscription rate rose sharply, and Maezono’s performance as editor-in-chief was highly lauded. Her talents were also evident in the way she leveraged and further honed Saeko’s scientific approach to investigative reporting.

Meanwhile, Saeko derived new opportunities to define herself as a writer through her work with Maezono, and the two divorcées developed a relationship of mutual support.

Maezono eyed Saeko while simultaneously browsing the dessert menu. “Besides, it would be such a waste not to apply your unique skills here. Of course, if you think it would be traumatic for you …”

Recounting the details of her divorce had been difficult for Saeko, even though the tone of the article had been lighthearted. At first, it was hard to comprehend why the topic was so painful—she certainly wasn’t still in love with her ex. But in the process of writing, Saeko was forced to face a new realization: her husband had been right about her unresolved feelings towards her father. She was forced to finally admit to herself that she had always compared any man in her life—her lovers, her husband—to her father. She glorified her father in his absence, building up an idealized image of him in her subconscious against which all other men paled. More evidence that she was unfit for marriage.

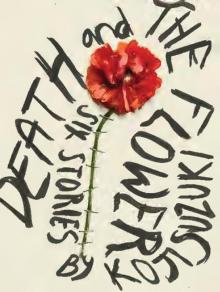

Death and the Flower

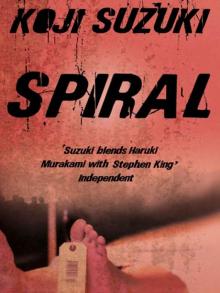

Death and the Flower Spiral

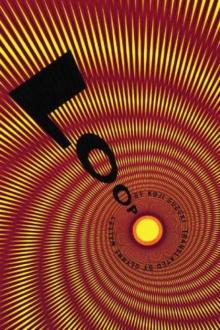

Spiral Loop

Loop Ring

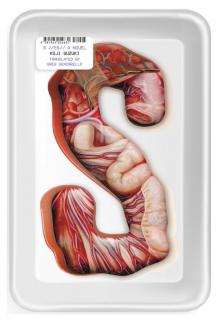

Ring S

S The Complete Ring Trilogy: Ring, Spiral, Loop

The Complete Ring Trilogy: Ring, Spiral, Loop Birthday

Birthday Edge

Edge Dark Water

Dark Water The Complete Ring Trilogy

The Complete Ring Trilogy